Chapter 3

In

The details of the marriage settlement which this Trollop arranged for his son John are interesting for they show how marriages were arranged primarily to suit the interests of both families, the wishes of the two people most concerned in the settlement being of little importance.

The marriage was contracted in 1448 between his son John and a daughter of Ralph Pudsey of Burforth, the Trollops gaining in the transaction 85 marks and in return promising lands presently owned by the senior Trollop, and any he should inherit to his son. A further clause however, stated that should the son die without an heir the land would revert to his father. The bridegroom was finally committed to his father’s jurisdiction until he was considered of reasonable age to govern himself. The penalty for breaking these conditions was forty pounds.

There is no record of how this John contracted in his minority spent his life or whether his marriage was a happy one. We do know that he was anxious that his soul should be saved for in his will dated 30th October, 1476 he bequeathed his soul to the Virgin, St. John the Baptist, St. Cuthbert, and all the blessed Company of Heaven, and desired that his body might be buried with the Friars Minor at Hartlepool to whom he gave ten shillings to sing a service for thirty massses for his soul.

He must have been a practical person for his will provides that his three daughters should each receive twenty pounds “to get them husbands.” His younger sons, Thomas and Andrew, and his brother Robert received annuities, while to his son and heir, John along with silver spoons and bed hanging he also bequeathed a large brass pot called “Old Thornlawe.” This last item was to play a large part in the fortunes of the family at a later date.

Another John Trollop, son and heir of the last named, married Catherine Sayer of Worsall on the 21st July, 1473, the bride’s father bearing the cost of the wedding and paying one hundred marks to the ’groom’s father in return for settlement of land on the son.

Andrew Trollop mentioned in the

will above was a warrior of some note in the reigns of Henry VI and Edward

IV. He fought in

Much of the information gleaned

about the Trollop family comes from wills. The son of John Trollop and

Catherine Sayer in a will dated 1522, instructs that

the “Thornley Pot” and the “Great Harry

Pot” were to be family heirlooms. His grandson Thomas instructs in

his will that he should be buried in his own Porch in

The next in line was another John Trollop, who, when he died left legacies of small amounts to a numerous progeny of young children. Being only minor gentry the Trollops possessed only a few personal and hereditary trinkets. Legacies of this type were common, for all the members of the family were dependent upon the person at its head, unless they became soldiers of fortune or entered the Church, there was no other way in which the lesser members could survive.

Unrest in the North during the

early years of the sixteenth century, aggravated by the act of 1536, caused the

closing of smaller monasteries and convents finally led to the Pilgrimage of

Grace. The revolt was not successful and as a result the Council set up

in

During the Reformation the wholesale destruction of Church property was wanton and indiscriminate. A point of local interest is the evidently thorough manner in which the commissioners performed their duties in the reign of Edward VI.

After they visited

“Upon William Blaxton of Coxso for so moche money bequeathed by one William Blaxton for the finding of a priest for xx years, whereof iiij years were to come at the tyme of the dissolucion of the colledges and chauntries at iiijli per annum xij.”

“Upon the executors of Gerarde Elysonof the paryshe of Kellowe, for the residue and remayne of iiijli for one years, which was given and bequeithed by the said Gerarde for the finding if a soule prieste in Launchester whereof wonted unserved one quarter xxs.”

Church monies left by will were taken and any balances due did not go to the relatives of the deceased but with confiscated in the name of the King.

Effective though the work of the

Council was, it could not prevent further trouble. Many in the north

disliked the Church which

The rising of the Northern Earls

was made more dangerous by the fact that

Many old families in the north were reduced to poverty through the part they played in the

Rising of 1569. The disturbed state of the bishopric about this time is shown by Bishop Pilkington (1561-1576). “The cuntre is in grate mysere and as the shireff writes, he can not doe justice bi anie number of juries of such as be untouched in this rebellion, unto thei be author quited by law, or pardoned bi the Q. Majestie. The number of offenders is so grate, that few innocent are left to trie the giltie.”

Because of his part in the rising John Trollop was included in the Act of Attainder of 1569. His life was spared but the estate became vested in the crown and was granted away to a Londoner. The society in the area was a closely knit unit, any newcomer would be a ‘foreigner’ and most unwelcome among the people of the area. The incident that follows is therefore quite believable.

Trollop was not the type of person to accept such a reversal without a fight. When the Granter came to take possession, old Trollop and several of his kinsfolk, disguised as countrymen met the Londoner on the verge of the estate, received him with marks of great respect as their new landlord, conducted him into the house, feasted him and made him drunk.

When the contents of the

heirlooms “Old Thornlaw” and “Great Harry

Pot” had taken full effect, and the new landlord reduced to a state of

insensibility, his tenants bound him hand and foot, placed him on horseback and

carried him to

In the absence of this landlord

Elizabeth I granted the Manor of Thornley and half

the Manor of Little Eden to Ralph Bowes who, however, came to an understanding

with the Trollops, which allowed them still to remain holders of the lease of

the nine closes in Thornley. These included Hanton Gathes, The Gore, the Milne Fields, Browne’s Close, Medowefield

and three fields. By one ruse or another John Trollop managed to keep his

hold on the estate during the reign of

About this time the Master and

Brethren of Sherburn made their last presentation to

the vicarage of Kelloe. The Reverend George Shadwell who had been curate at Houghton-the-Spring and at Trimdon, was presented to the vicarage. Bishop Barnes

refused to institute him and claimed the right himself. Eventually he

made the presentation in 1579, and the Bishop of the diocese has been the

patron of the living since that time. Shadwell had definitely embraced

the Roman Catholic faith, and had proclaimed him conversion in

The Trollops were confirmed Roman

Catholics and during

At his trial Thomas Trollop was

released on the charge of “conveying” but recommitted to gaol for persistent recusancy.

He stated firmly that he positively refused to say “amen” to any prayers

said in a

The Trollops were not deterred by the outcome of the trial, for their activities on behalf of the Catholic part of the population continued. The most important priests in the area at the time were Richard Holtby, George Errington and John Carr. All of them stayed for some time at Thornley Hall.

In 1593, Holtby who was staying at Thornley Hall, went with John Trollop’s eldest son to a nearby village to baptise a young child. Returning to the house they realised it was surrounded and that the pursuivants were searching it. They were seen by the guards, but taking to their heels they reached a nearby wood and secreted themselves in it. They spent two days in the wood before they decided it was safe to emerge. Mr. and Mrs. Trollop with one of their sons and a niece of thirteen years and two servants remained shut in the house for three days until the guards became tired of waiting and finally left. George Shadwell, previously mentioned, was connected with Holtby.

It was know locally at the time

that “the Dene” at nearby Castle Eden

possessed a cave and that Roman Catholic missionary priests sailing to

Legally the Manor of Thornley no longer belonged to the Trollop family, although John Trollop had by various means managed to maintain his hold on it. In James I’s reign the Manor was granted to Edward Bee and John Lavie of Camber, who gave information against John Trollop for intrusion into the lands and Manor of Thornley, but because of his great age, Trollop was granted the case for life.

On his death in 1611, the

struggle for possession began once more. His grandson John, who succeeded

him as heir of entail, managed to establish his rights against the Crown by a

trial at Bar before a Jury in

The estate that had been

difficult to recover was inexorably mouldering away

when an event occurred which precipitated the downfall of the family. On

When the Civil War began in 1641,

the elder Trollop espoused the royal cause and two of his sons were killed in

the service of Charles I and Charles II at Wigen and

The parish of Kelloe, of which Thornley was a part, favoured the King’s cause and suffered because of this, for a Parliamentarian army under Leslie encamped on the slopes of Quarrington and commissioners sat to sequestrate the estates of royalists in the district.

The house and furniture of the Trollops was seized by the sequestrators and the grandson’s goods were also taken. The list of goods illustrates how few were the possessions of a middle class family at that time.

“Inventory

of the estate real and personal of Mr. John Trollop of Thornley,

Esq. Papist and of Mr. John Trollop the younger,

The Parliamentarians appear to have gained complete control in the area, for in the place of John Liveley, the vicar at Kelloe, a Presbyterian, Thomas Dixon was installed and soldiers were billeted in the surrounding houses and farmsteads. At nearby Cornforth a Scottish army was encamped and here the plague broke out.

The following extracts from the Church records bear out the facts that an army and the plague were present in the area during the years of the Civil War.

“In 1644, April 8th,

were buried “a pegrin” (wanderer), a South

Countryman, and a souldier, taken by ye Scotts at

“In 1644, November 4th, a Scotsman, a souldier, dying at Cornforth, the souldiers themselves buryed him without any Minister or any Prayer said on him.”

“1645, October 29th, Thomas, son of Robert Weedefeild, dying of plague at Cornforth was ther buryed. On November 11th, William his son, and on November 13th, Elizabeth, his daughter, were also buryed, having died of the plague.”

“1646, February 20th, Thomas Writ at Cornforth, slayn by souldiers.”

“1646, February 22nd, Isabell Casse spinster, a Scotch woman buryed..”

Families who had supported the king during the Civil War and who had suffered as a result, naturally expected that the Reformation would see them restored to their former prosperity. Many however did not regain their possessions and the Trollops, ardent Royalists though they had been, found themselves at the Restoration reduced to the family mansion and one third of the family estate.

In 1668, the death of the elder

John Trollop reduced the family to two people, his son and grandson. They

clung to the estate till the death of John Trollop the younger in 1678, and on

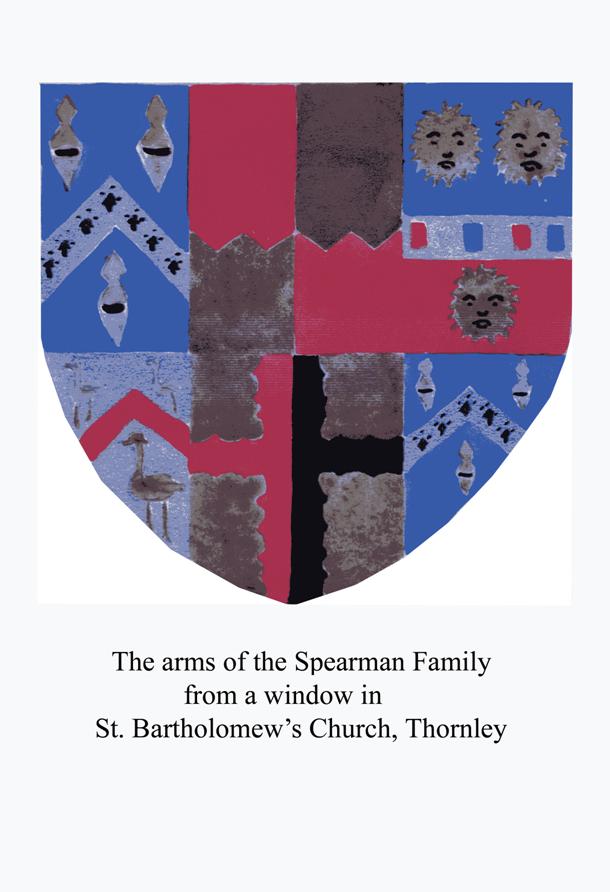

that sad event his father sold the Manor and remaining lands to John Spearman

for the sum of £1,500, and retired to